When a haunted Appalachian boarding school begins to twist under the influence of a supernatural voice, seventeen-year-old Adelaide must decide whether to stop the creature calling to her—or surrender to a legacy that might destroy her and everyone she loves.

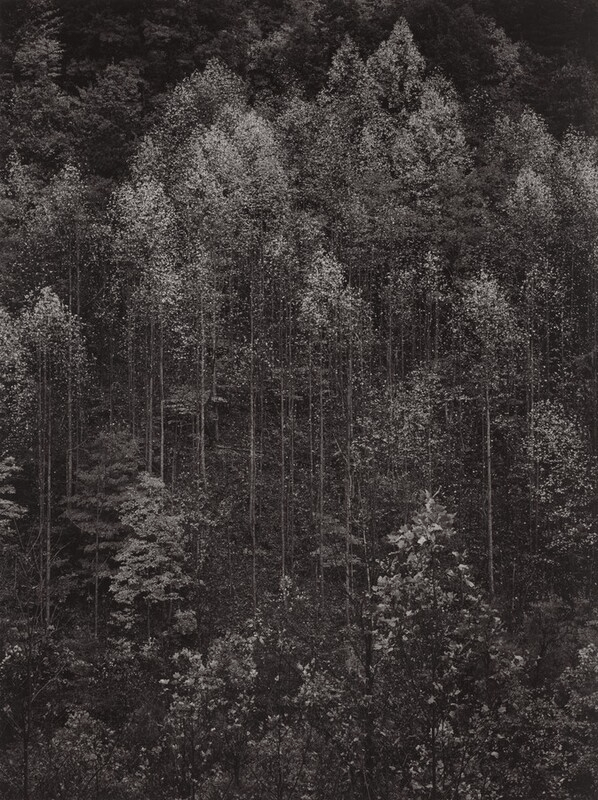

Set against the eerie backdrop of a Southern girls’ boarding school in the Smoky Mountains, Whistler in the Stacks is a 98,000 word Young Adult Southern Gothic novel that blends folklore, dark academia, and the emotional complexity of growing up. It will appeal to fans of A Lesson in Vengeance by Victoria Lee, The Buried and the Bound by Rochelle Hassan, and The Wilderwomen by Ruth Emmie Lang. With its focus on friendship, girlhood, and reckoning with inherited power, this book is for readers drawn to lyrical storytelling, haunted places, and the magic that hides in history.

If you’d like to listen to music to get into the spirit of the novel before/during reading the sample below, follow the Spotify link here.

✶

Whistler in the Stacks Opening Poem & Chapter One:

We buried him in earth and peat.

Have you heard my lover’s dark tale?

My William, he was oh, so sweet.

That man put a rope ‘round his neck,

And made me watch him swing and swell.

We buried him in earth and peat.

Unknown to him, his lifeblood’s speck—

Our love-born secret not to tell.

My William, he was oh, so sweet.

Now all my life is forced to wreck,

Our future gone after he fell.

We buried him in earth and peat.

My William’s headstone sits erect,

While I damn another to hell.

My William, he was oh, so sweet.

Now in the library he treks,

Trapped by the looming blues and bells.

We buried him in earth and peat.

My William, he was oh, so sweet.

Chapter One

It was an unspoken rule: no one goes into the library alone. Not a footstep inside, not a breath of unshared air. That is, unless someone was looking to be murdered by him.

That’s how we began the tale every year—Edythe and me—as we all huddled under someone’s covers, holding a contraband flashlight in hand and wishing for the warmth of the fireplace downstairs, no matter the temperature of the August air outside. It was a tradition, and us Holloway girls were known for such things.

New freshwomen poured into our hallowed, and probably haunted, halls every year, vaguely aware of his story: the one told on bleak nights when the rain seemed to fall in endless sheets down the windows and when the chill in the air could hardly be shaken from our bones.

They would change out of their freshly pressed, plaid skirts and puffy white blouses and tiptoe down the halls, pitter-pattering until they made their way to an upperclasswoman’s door. This custom was said to have been passed down for over a hundred years, and as newly initiated juniors, Edythe and I were ready to spin more yarn.

With sheets held firmly above our heads, we began to recite the poem in perfect unison, peering at all of the young faces before us: “We buried him in earth and peat. Have you heard my lover’s dark tale? My William, he was oh, so sweet…”

We theorized it was only a story meant to keep the pestering sixth graders out of our way in the library, but I wasn’t sure. It likely dated back to sometime in the 1800s, as all good ghost stories do, but no one knew why William was hanged, or why he was so sweet. Who were his enemies? Who was the woman? His wife? A forbidden lover?

It wasn’t really a stretch to say that campus in general was inhabited by ethereal beings. Nestled in the Smoky Mountains, Holloway’s Preparatory Academy for Young Ladies used to be a hospital to treat scarlet fever patients. And if that’s not spooky enough, generations of Holloway women claim encounters with those who died in the various dormitories and classrooms that are now dedicated to the sheltered learning of so many decent, young women.

Just like most of the girls here, Edythe and I were forced to attend because our mamas went here and their moms and their grandmothers and their great-grandmothers and back and back and back into the abyss that is the never-ending history that encompasses most Southern families.

I didn’t mind, really—the long, hyphenated names or the drawling drivels of my peers and parents—I could deal with all that. But with Holloway itself…sometimes I couldn’t sleep because of the deafening presence of those from the great beyond, including Sweet William.

All of the girls in my class tried our best to find information on him and why his tormented spirit decided to roam the halls of the second floor of our library. The general lack of technology and know-how at our school limited our quest: no phones, no TVs, no computers, and even no radio allowed.

Once on the twisting, brick-trodden grounds of Holloway’s Preparatory Academy for Young Ladies, anything connecting a girl to the outside world was strictly prohibited. We had running water and the electric light, but anything past that was usually labeled as contraband and thoroughly eliminated. So, once we left the clutches of our school for the summer, nobody wanted to bring Sweet William home with them.

At one point we managed to smuggle in a record player, but even so, we couldn’t use it very often for fear of getting caught by the hounding matrons who patrolled past our rooms. Despite being somewhat arcane, I was more bothered by the assumed demons that walked to class with us. I tried not to dabble in the darkness that lurked within the grounds of Holloway, but on the first night of every year when the locks clicked shut and the wind mussed our cotton curtains, I followed suit with tradition.

So, on the first night, freshly moved into our dorms, we sat there with our fellow ladies, some with their grandma’s curlers in their hair, and began the school year in the proper way: terrified and surrounded by our friends in that ancient, creaking dorm room.

𓆸

The library wasn’t even that whimsical, but Edythe and I talked about it like it was a mythical world. Its crumbling brick exterior, powerful columns holding it upright, the way the halls melted into one another, tilted floors that groaned, carrels that blocked out all vision, the way the sun beat through the windows and illuminated the stacks…

At this point we had the girls like Lincoln Logs, building the horror in their minds and inculcating that no one, and we meant nobody, should walk into that building by themselves, let alone the second floor.

“I still don’t get it,” one girl whispered, her white nightgown stark against her summer-tanned skin, “What’s so scary about some old man walking around the second floor?”

“Haven’t you heard about what he’s done to…” a dramatic pause, “done to innocent first years like yourself?” pleaded Marianne, one of our friends.

A laugh met her somber response, “What, did Sweeeeeeet William kill someone there?”

In a lovely harmony, Edythe and I nodded, my best friend murmuring, “And they didn’t find her body until someone noticed the blood splatter on the window behind her carrel.”

The small sixth grader shifted, making the bed frame moan. Her voice raised, “How long ago was that, a hundred years?”

Marianne spoke up, “Don’t tell her! It will only scare her.”

“I don’t know,” I mused, twirling a piece of hair and tucking it behind my ear. I inhaled, leaning so close to her that our foreheads almost met. “It might be safer if she knew. Maybe then she wouldn’t poke around the library for fun. You know what happened to the last girl that did that…” I trailed off.

“How long ago?” a different twelve-year-old said in a lowered voice.

Edythe tried to hold back a giggle, “Maybe Marianne is right, Adelaide, if they know, they might not be able to sleep tonight. Especially if their rooms are on the east wing and face the library. What if they see something through their window?”

“Come on, just tell us. If you don’t have any proof of some fake ghost killing someone then there’s no reason for us to be scared,” a nimble ninth grader grumbled, clearly not buying our story. Clearly, this wasn’t her first rodeo.

Edythe and I locked eyes and winked at each other. “Seven years ago, on this very night,” we said together.

“If you listen carefully,” Marianne interrupted, “you can always hear her screams in the middle of August, just around this time.”

Another girl in our grade, Charlotte, continued the tale, “We were just starting school here like all of you, and we had been told the story of Sweet William. But, alas, they told us because it was a tradition—not because they believed in him. That was their mistake.” She paused, wiping a fake tear from beneath her eye, “So little miss Joanna Sayner waltzed into the library,” she sniffled, “and never walked out again.”

Someone farther back chimed in until almost every girl my age added another piece to the story, “And we had just had dinner together and were becoming the best of friends.”

“I heard she hadn’t met her roommate yet.”

“Well, I was told there was something off about that girl…”

“My mama said hers was devastated.”

“Sometimes I hear her feet walkin’ above me in there.”

“You think her ghost is in there too?”

“Well if it was, I can’t go back in—”

The girls got louder, and the heat of their breath mingled under the sheet, filling our circle with a fervent electricity, bringing Joanna’s story to life. That is, until we mistook the sound of a creak for the usual whimper of the old building in the wind.

No, this one was too close. None of us were paying attention as Madame Elinor Patterson, headmistress and sardonically divine, jingled her key inside the lock and pushed open our door.

A silence—akin to when someone is at the precipice of a cliff and the wind stops and they’re surrounded by the immensity of nature and the possibility of death—filled the room, and the final groan of the door hushed Joanna’s tale as Marianne began, “It’s too bad…”

“Too bad she didn’t listen,” finished Madame Patterson.

I could feel the pulse of the air change. Those younger than us feared punishment for being out of their rooms, just as we feared the retribution of such a lawful woman.

Glancing downward, I couldn’t raise my head out of the sheet and meet those beady eyes. No one could. So, we all kept our heads down. M.P. likewise remained in the doorway, no doubt with her hair twisted up tight enough to cut off her head’s circulation. At least, we guessed that’s why she was so mean.

“If you’re all going to be so silent, I suggest that you use this time to get to bed. You need to be well-rested for your first day of classes tomorrow, and this nonsensical conversation will keep you up all night.”

“Yes, Madame Patterson,” all of us muttered.

“If I happen to hear another peep out of any one of you, about that silly ghost story or any other absurdity, you will find yourself sleeping in my office on the first floor.”

As she turned to leave and we began rustling underneath the sheet, M.P. grasped onto the door handle. In the quiet, it was almost as if we could slightly hear her head turning full circle.

With a final breath, she sighed, “And Ms. Collings and Ms. Holloway, I would expect more from you two. Carrying on this ridiculous tradition is beneath you and your family connections to this school.”

“Kincaid,” I said under my breath, knowing I would rile her.

“What did you just say?”

The whites of my classmates’ eyes shone as they all turned to me, and I spoke up. “My last name is Collings-Kincaid, not Collings.”

“Do you dare talk back to me, Ms. Collings–Kincaid? Would you like to sleep downstairs tonight? The cot is not prepared because I did not believe disciplinary action would be taken so soon. But, of course, I can always hand you a blanket to sleep on the floor.”

I let out a hard breath before dragging the sheet from my head and looking at her moonlit face. Ghastly features met my own as I pulled up my nightgown, sitting straight up, shoulder blades back. “If you wish to call me Collings, you would be half right. I was only meaning to tell you that it’s a hyphenated last name, and my family connections to this school would be very angry if you left out the second half.”

M.P. scoffed as I finished, “Now, if you would allow me, Madame Patterson, I would kindly like to escort these young and error-free girls to bed. They’ve been scared enough.”

I held back a smirk as Edythe purred below me, “Yeah, scared enough by Thou Holiest Ghost, Madame Patterson.”

Less amused, M.P. looked me up and down, taking in every swirling atom of my being, from the curlers in my hair to the lace of my night gown, with such a look of disgust that I thought her frown might fall off. She blustered again, retorting, “Ms. Collings-Kincaid, if you speak to me like that again, you may find yourself in my office. For now, I suggest you and Ms. Holloway,” she nearly spat, “bring these girls to their rooms and make sure they stay there.”

I nodded, silently grasping Edythe’s hand with a squeeze of victory and sweetly said, “Of course, Madame. Goodnight, and peace to you.”

As she finally left, M.P., in Holloway tradition, sighed, “Peace to you.”

Pulling off the sheet all the way, I stared at all of my newfound sisters, putting a finger over my lips and waiting until M.P.’s footsteps trailed back down to her own room. After I heard her lock snap, I smiled. “Where were we?”

Marianne replied, “We were just leaving. Come on…” She pulled on the arm of the girl closest to her. The girl, whose name I didn’t t know yet, didn’t budge.

“But we didn’t even get to the best part,” implored Charlotte.

Edythe answered in mock exasperation, “I think they’ve had enough.”

“But what if they see Joanna or worse. What if they see him?” I said, cocking my head to the side with fake worry.

It was hard not to grin, but we stayed serious. These girls were new, and they needed to respect their elders. They needed to know who to talk to when ghosts began to walk alongside them. So, we decided to finish the night like we had done so many times before: by saying a chorus to ward off the otherworldly.

Little did they know we created the chorus in sixth grade, just after Ms. Joanna Sayner transferred out of our school to go somewhere normal: a real school where friendship and studies were not equivalent to ancient buildings and ghastly tales. None of us kept in touch with Joanna, but we heard she went back to Georgia and attended some prep school there. Nonetheless, she was the perfect fuel for our frightening fire. Because, even if the new girls did not believe in Sweet William, surely they would believe in us.

We began, alternating lines of a long-since memorized verse, encircling our new initiates into the world of Holloway, binding us in song and skin as we grasped hands. Tongue-tied Amelia, a girl in our class known for wicked brains and utter poise, started,

“To keep away from Sweet Joanna,”

“And Sweet William too,” Charlotte continued.

“Cross your arms,” I said.

“Close your eyes,” Edythe sustained.

“And say this a time or two:” Marianne furthered.

We spoke in cold unison:

We, the women of Holloway,

Reject your presence on this day.

And as such, we beseech you,

To leave us be and to never do,

The vile crimes,

We’ve heard of you.

Take your leave, and let us be,

Strong and unflinching friends, eternally.

A whisper of wind rattled a window finish our unblessed verse, acting as the perfect catalyst for us to disembark from our room and guide the younger ones to their own. Some static from the fresh linen frizzed our hair or shifted our curlers, but other than that, everyone left the room unscathed.

Edythe and I took a gaggle of seventh graders and dropped them off at their respective dwellings. The first room we stooped at, Cecily and Faith’s, was a mirror image of our own. A single window separated the two girls’ beds, each held up by a simple, chestnut frame with a woven, circular headboard. Their sheets, white and embroidered with lace, were folded back under thin quilts, and the olive trunks at the end of their beds were fastened tight.

The girls shimmied their way under their covers, breathing in deep the sweet and fleeting August air, savoring it before it vanished.

Edythe and I began to make our way out. We had ten more ladies trailing us. Yet, on second thought, I turned on my heel and walked back in and said softly, “If you ever need us to smuggle in blankets for you, just come up to our room and ask.”

“But…Isn’t that contraband?” Faith asked while Cecily, ever so innocently, knitted her eyebrows together.

Edythe and I huffed a slight laugh in response before winking at the girls, making our way out as we slid the door shut.

We continued in the same way down the seventh grader’s hall until we ran out of tired girls to put to bed and offer our clandestine services for basic human needs. We kept stashes of snacks, blankets, water bottles, and other contraband items hidden throughout the building and in the depths of our trunks under a false bottom, crafted ever so generously by my brother, Absalom, who attended yet another boarding school a few miles south of Holloway.

Of course, boys were forced to attend a separate institution, and many had strange, biblical names. Whether our shoulders would be too distracting, our words not holy enough, or we were just too smart for them I didn’t know. But, I found solace in the unflinching embrace of my Holloway sisters, especially when the night closed in with all its dusky glory.

Edythe and I made our rounds, but before locking ourselves in for the night, we paused in the center of our landing, overlooking the common room far below with its wormy chestnut walls and ivory furniture. Exhaling, I supposed, “We’re back.”

I turned my head and Edythe smiled, brushing untamed strawberry ringlets out of her face. She reached to squeeze my hand, and I grasped hers. In all of our years together at Holloway, she had become my unspoken other half, part of a lone sisterhood that blossomed after both of us were shipped off by our families to boarding school.

She began to speak, “And now that we’re back…”

We finished together, “When are we going to sneak out?”